On July 1, a

new anti-spam law went into effect in Canada that significantly changes how commercial email messaging operates. The most significant feature of the Canadian Anti Spam Law (CASL) is that commercial senders must obtain express permission (i.e. opt-in) in order to continue sending commercial email. (There is a 3 year transition period where senders who have previously obtained implied consent can continue to send mail while they obtain express permission). The penalty for not complying with CASL is significant--up to $1 Million CAD for individuals and up to $10 Million CAD for businesses. Starting in 2017, recipients can sue senders for not complying with the law.

CASL is very different than other legislation like

CAN-SPAM in the US, where senders can send commercial email until users opt-out by notifying the sender they do not wish to receive the messages.

We support any legislation that makes it easier for recipients to get the messages they want and avoid the messages they don't want. However, it probably won't lead to the end of spam. We think CASL will have the following effects:

- Spammers who already flout laws like CAN-SPAM will likely not change their behavior.

- Well-prepared commercial senders will have to do a lot of work to clean up their email lists and obtain express consent, and will likely lose recipients that wish to receive mailings but forget to actually opt-in.

- Unorganized commercial senders will inadvertently violate CASL and some of them will be penalized.

Let's go through each of these points.

Although CASL raises the bar for well-behaved commercial mailings, spammers have been ignoring existing legislation for years. Along with honoring opt-out requests, CAN-SPAM in the US requires:

- The message headers do not contain false or misleading information.

- The email clearly identifies itself as advertising.

- The email contains an opt-out mechanism and (physical) contact address.

A quick look in your spam folder will find plenty of examples of messages that violate all of these rules. The difficulty in identifying spammers and prosecuting them under existing legislation, relative to the financial rewards from spamming, makes the risk/reward tradeoff an easy one for spammers to make. Until that tradeoff changes, additional legislation is unlikely to have a big impact on spam volumes.

On the other hand, legitimate commercial senders must operate within the law, and to comply with CASL they must reach out to every recipient on their mailing lists and ask for permission to continue mailing. Some companies have tried to sweeten the deal with

prizes and other incentives, but many recipients that truly want to continue to receive emails will forget or be too busy to opt-in.

Although many senders will go through the effort it takes to validate and obtain permission for their recipients, smaller companies with fewer resources will likely have problems contacting and obtaining consent from their customers. Until 2017, the Canadian Radio-Television Commission (CRTC) is responsible for investigating complaints and enforcing the law. Hopefully they will use common sense and discretion when deciding who to prosecute under CASL. However, after 2017 recipients can bring civil cases directly against senders. This path removes that layer of discretion and could lead to abuse of CASL within the court system.

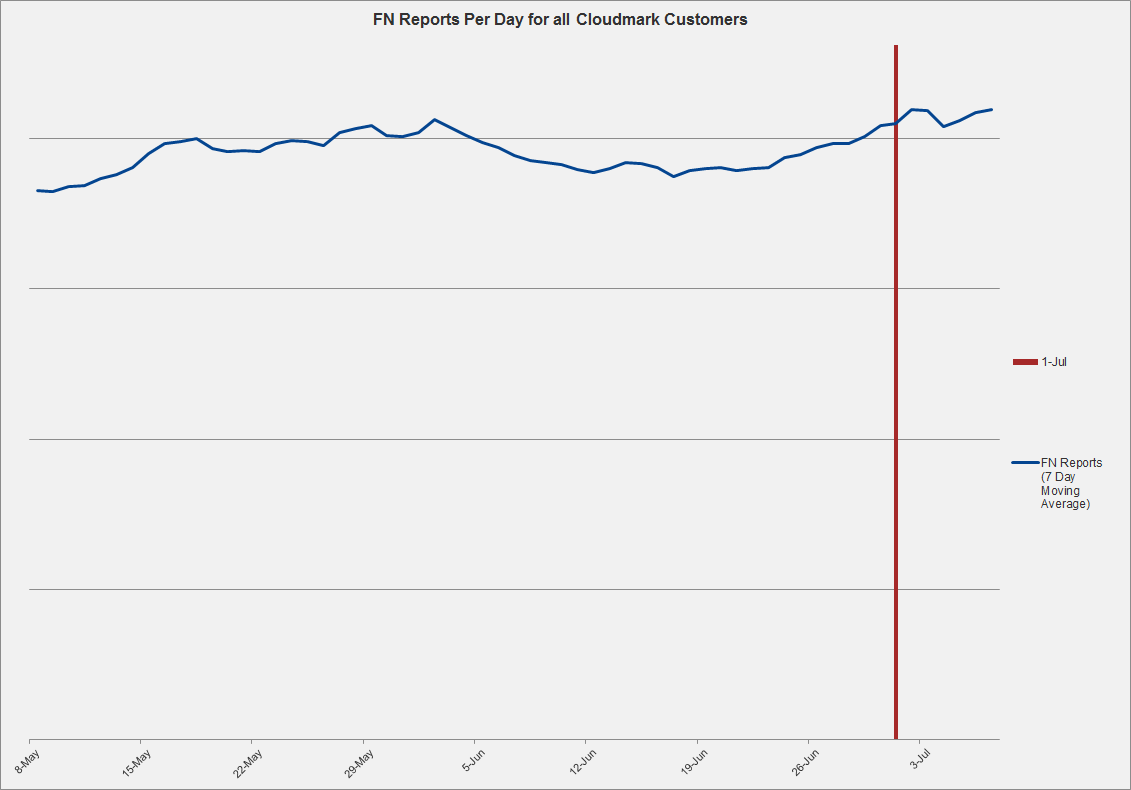

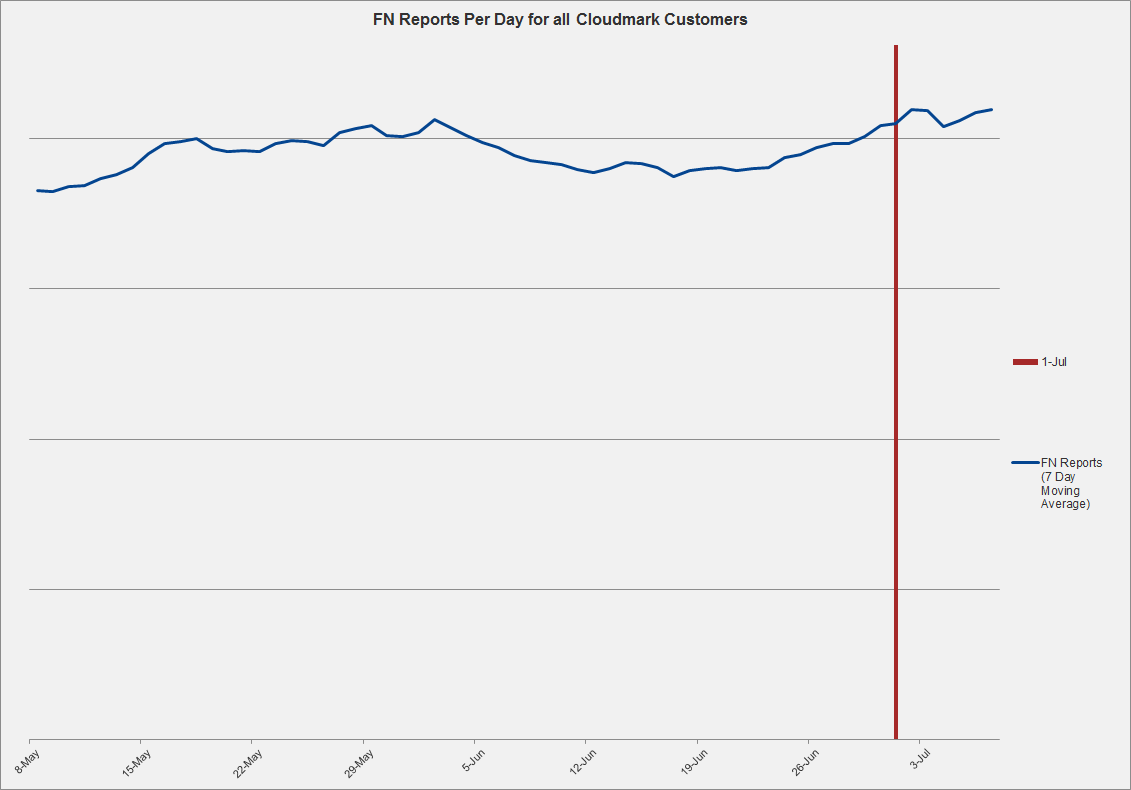

What we probably

won't see from CASL is a significant reduction in spam volumes. We certainly haven't seen any decrease yet. Here is the total number of Spam Reports (also known as False Negative or FN Reports) we have received per day via our Global Threat Network since May 1, 2014. We graphed a 7 day moving average to smooth out day-to-day changes. There isn't any significant decrease in spam reports:

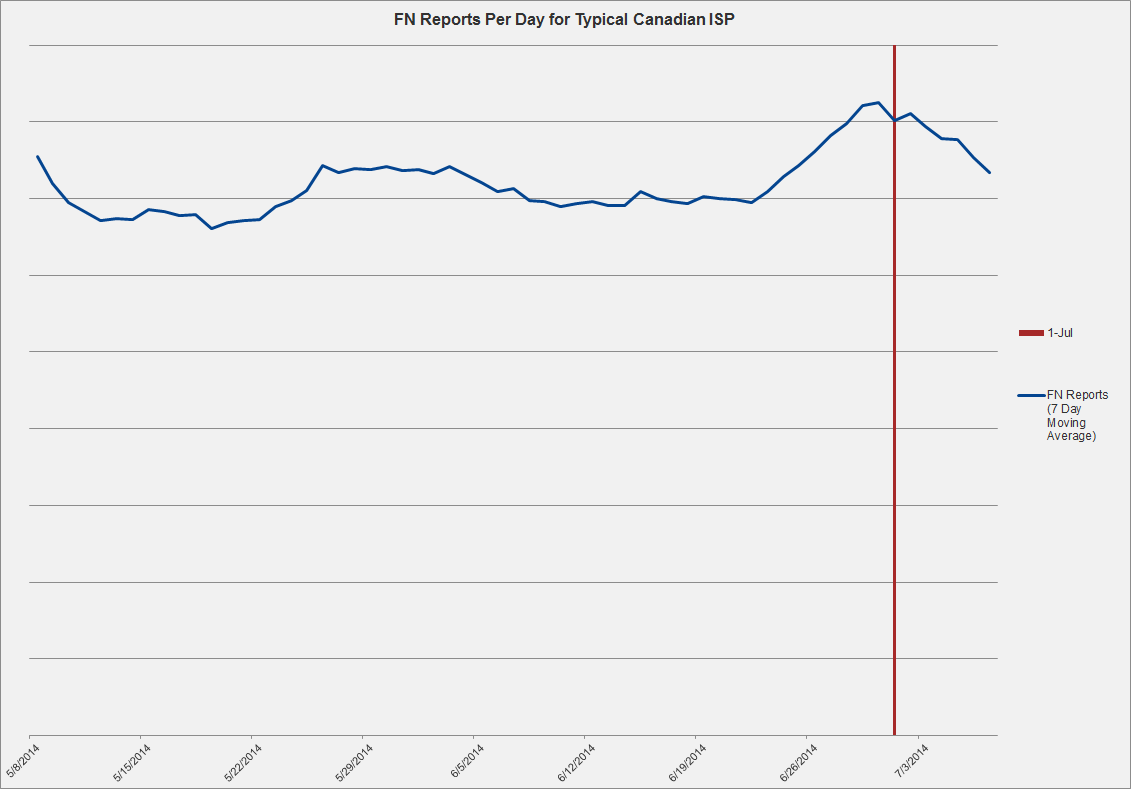

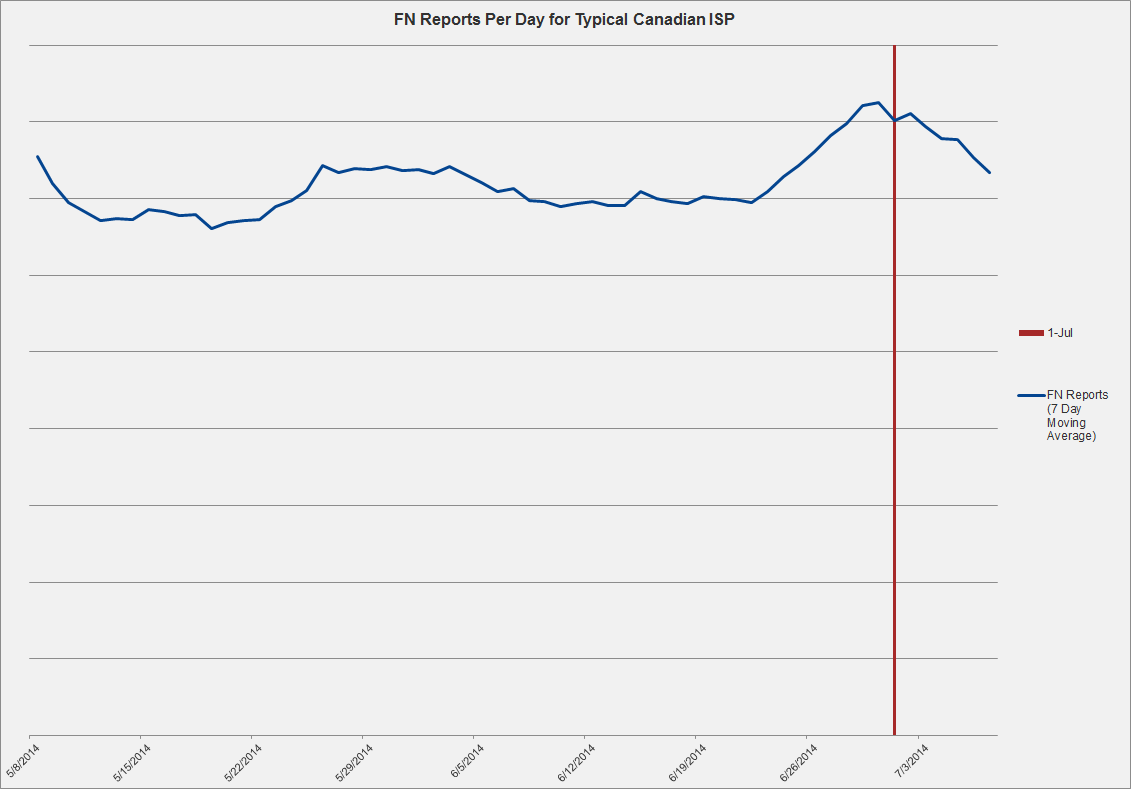

Maybe if we look specifically at Canada we'll see a difference. Here is the total number of spam reports per day for one of our Canadian ISP customers:

Again, there isn't any visible decrease. If anything, there may an

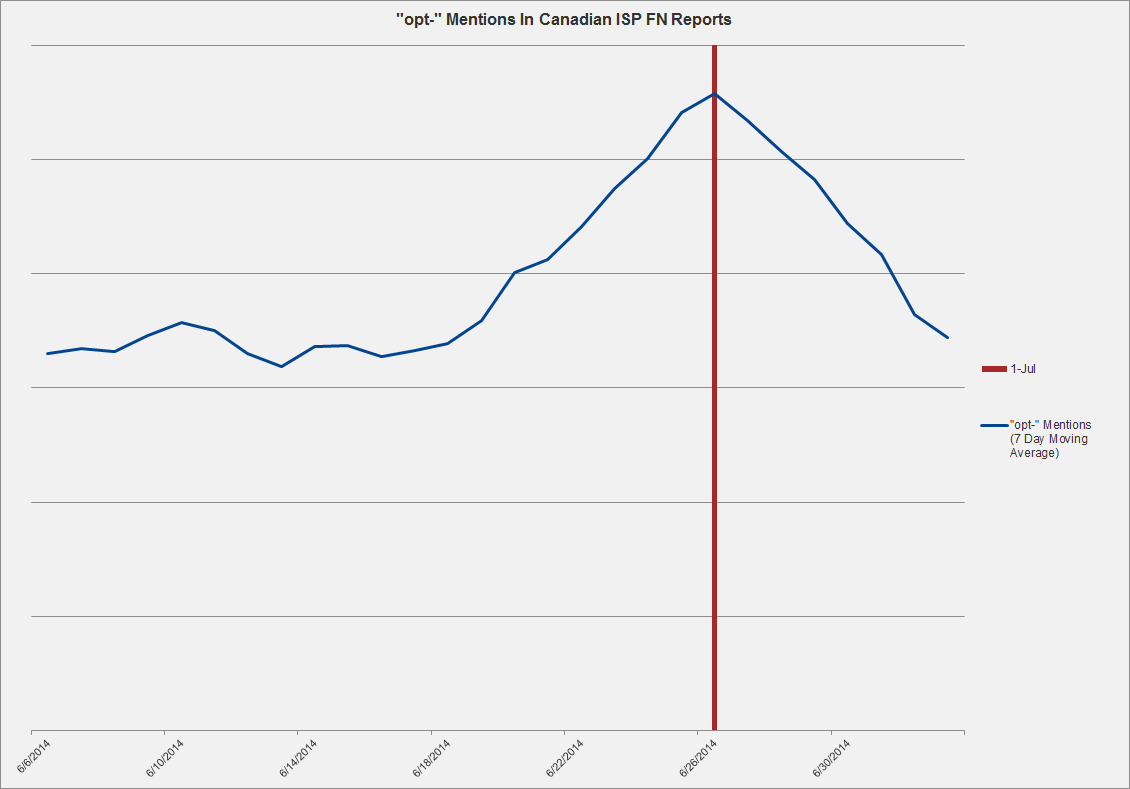

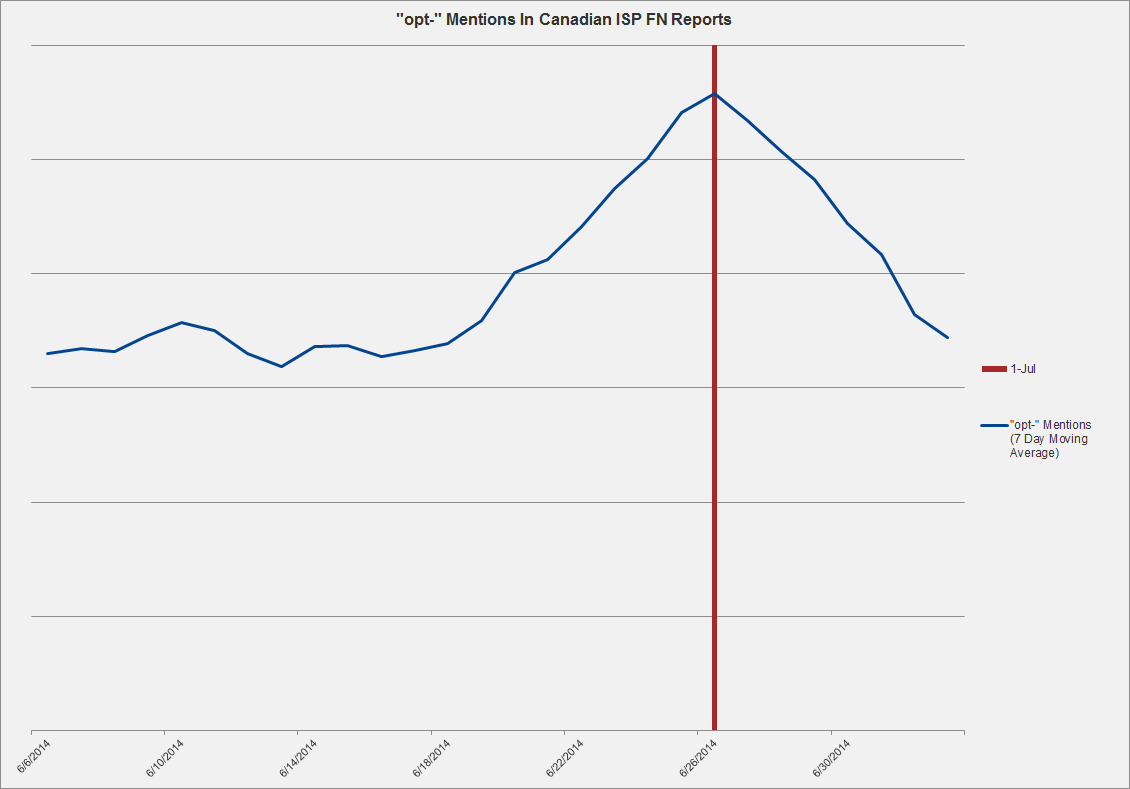

increase in spam reports in June. One possible reason for this is that people are reporting opt-in requests from Email Service Providers (ESPs) as spam. To help determine this, we counted the number of times "opt-" was found in all FN Reports for that Canadian ISP for the month of June and early July:

There definitely is increased use of "opt-" the week before July 1 and a big drop after July 1. The top of the peak on July 1 is around 40% above the baseline for most of the month of June. That validates the theory that senders were sending more opt-in requests in June, which unexpectedly resulted in a temporary increase in spam reports.

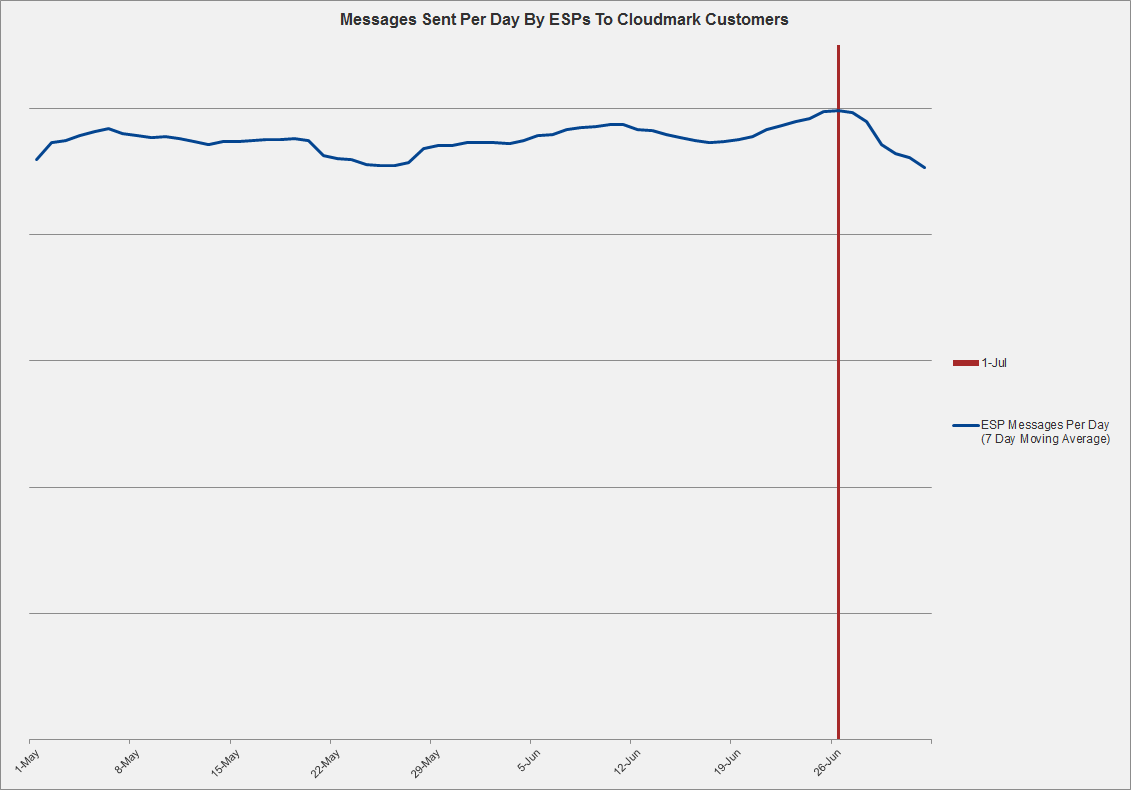

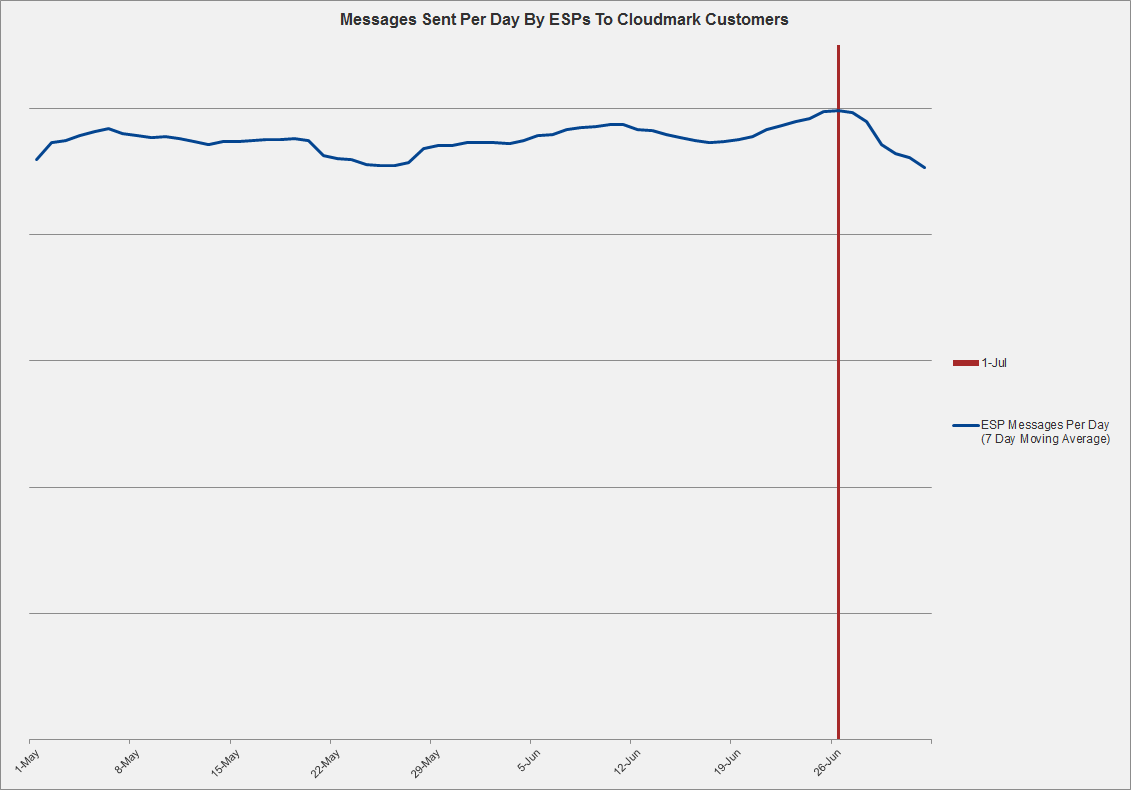

Although we saw more opt-in requests at one Canadian ISP, we aren't seeing a big jump in the number of messages sent by Email Service Providers (ESPs) globally. Here is the number of messages sent per day to our customers from IPs we know to be used by ESPs:

The message volume looks fairly steady.

One challenge that the CRTC will have in enforcing CASL is knowing the difference between well-intentioned senders that make a mistake and senders that are flouting the law. Even diligent senders that have audited their recipient lists to obtain opt-in confirmations might make a mistake and send a message to a non-opt-in recipient. This is not the same class of violation as a sender who never bothered to obtain opt-in confirmations and continues to send repeated mailings to many recipients.

Cloudmark has data that could inform those decisions. As part of Cloudmark Sender Intelligence (CSI), Cloudmark monitors poor and suspect reputation and also tracks the reputation of legitimate well-behaved commercial senders in order to differentiate them from misbehaving commercial senders. We correlate a variety of factors including both spam trap hits, volume of trusted end user complaints (hitting the “This is spam” button), reputation of the reverse DNS of the IP, reputation of the IP block that the IP is part of, and traffic volumes over time.

Overall, we think CASL is a good step in the right direction, as long as its enforcement is limited to repeat offenders who ignore the law.