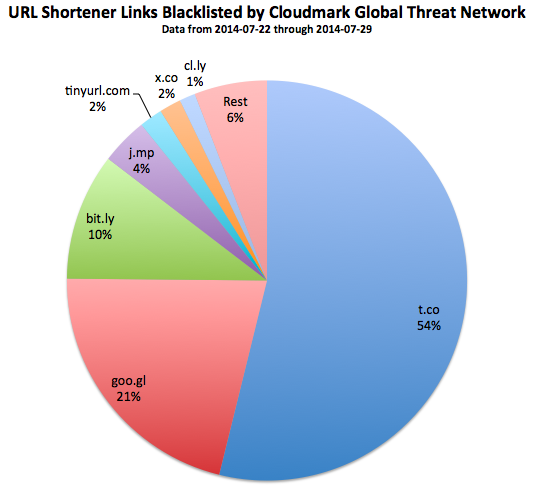

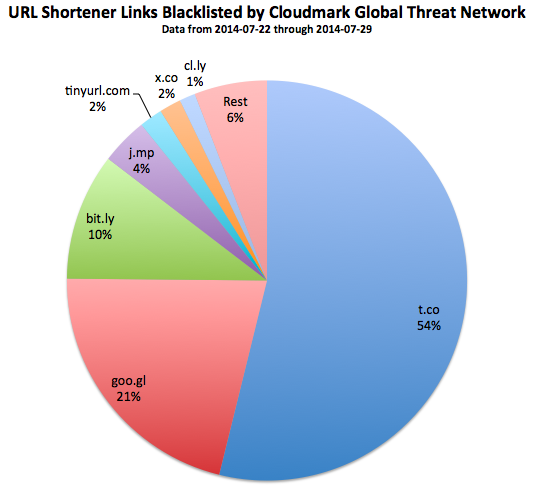

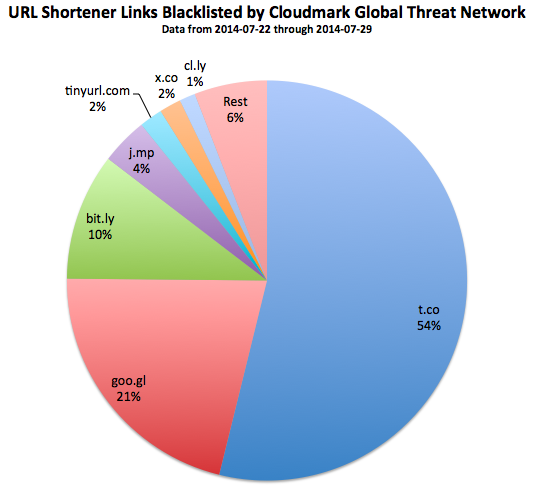

URL shorteners such as bit.ly, goo.gl, and t.co have long been used by spammers. They provide an unlimited source of different URLs which can be used in emails to disguise the final landing page. The major companies providing this service all have anti-abuse filters in place to attempt to control this sort of malicious activity. However, some are doing better than others. Currently, more than half of all shortened URLs blacklisted by Cloudmark come from Twitter’s t.co service.

I believe a single spammer is responsible for the vast majority of this t.co abuse. Let's take a look at what he is doing and how he is evading Twitter's anti-abuse filters.

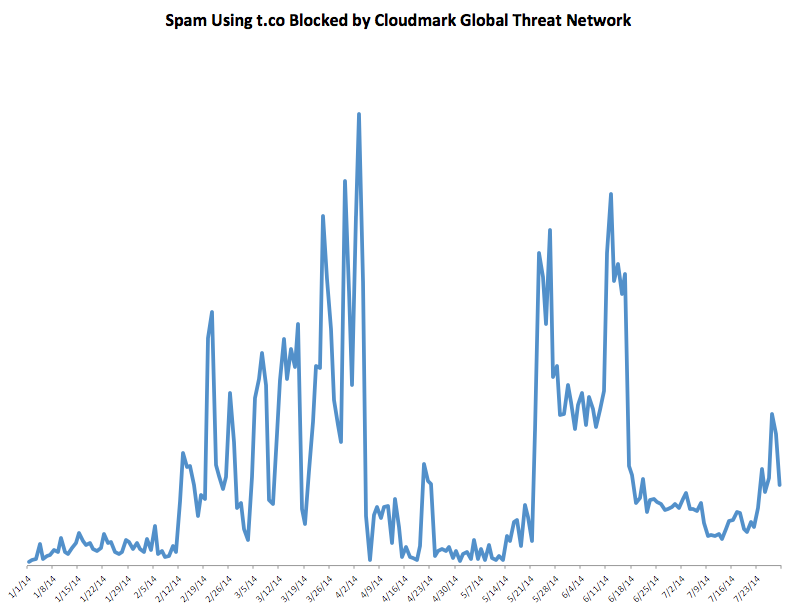

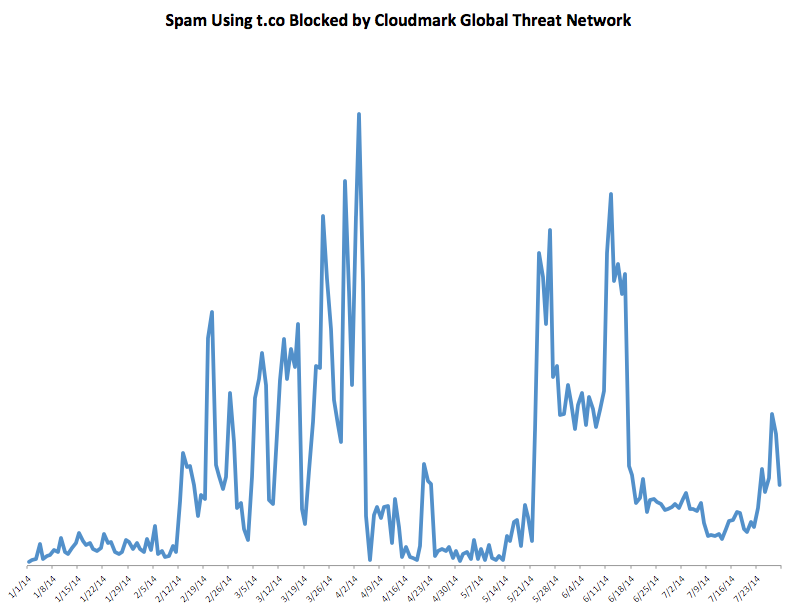

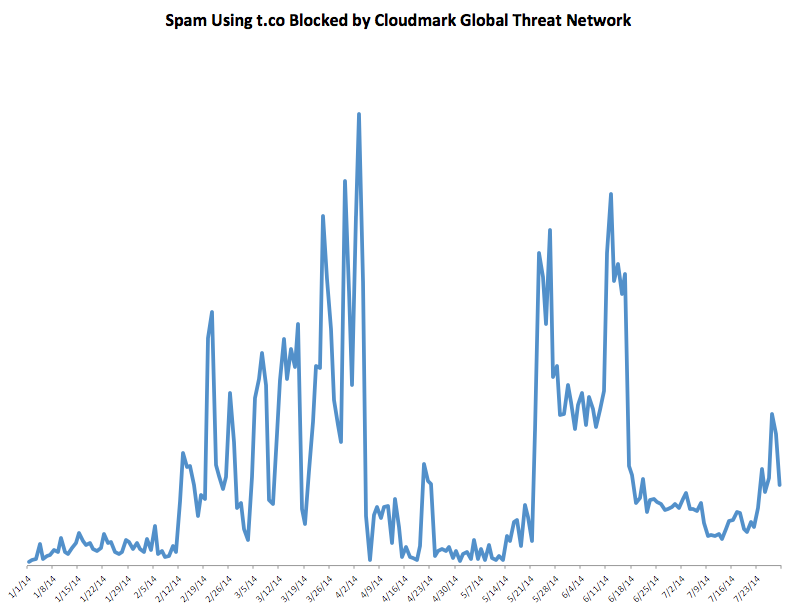

Spam using t.co tends to come in surges lasting four to six weeks. It may be that this is the time that it takes Twitter to detect a new attack, work out what is going on, and update their anti-abuse filters to deal with whatever method is being used to bypass them. Here's the year to date chart of spam volume using t.co.

As you can see, there was an attack that began on February 12th and was brought under control by the start of April, and another that began on Mar 22nd that was substantially reduced four weeks later. However, the spam level did not fall back to anything close to the historic lows, and in the past week or so we have seen another smaller spike. Since we have been seeing moderate or high volumes of t.co abuse for several months now, I decided to take a close look at what was going on.

I took a sample of 1,200 t.co links found during the past week in emails that were reported to the Cloudmark Global Threat Network as potential spam. Note that we are not monitoring Twitter's own social network, so we do not have visibility into the thousands of t.co links used every day in tweets. I looked to see where the links ended up. Of those 1,200 links, 81, or about 7%, were legitimate uses of a URL shortener, usually from a tweet that had been forwarded by email or SMS to someone who had then clicked on the

Report Spam button. Only 59 (about 5% ) had been detected as malicious by Twitter first, and redirected to a warning page at the time of analysis. The remaining 1060, 88% of URLs, still redirected to a web site already flagged by Cloudmark as a spam landing page.

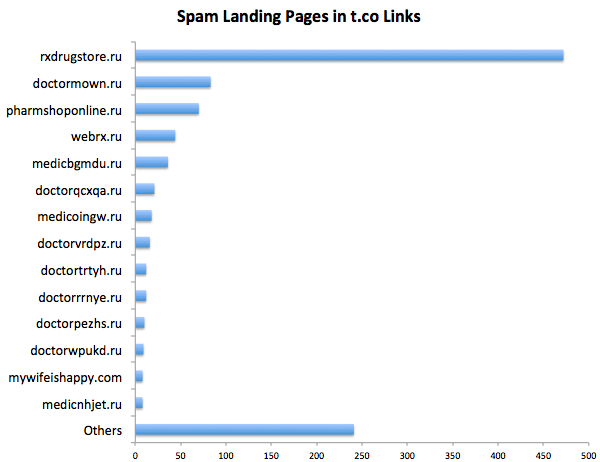

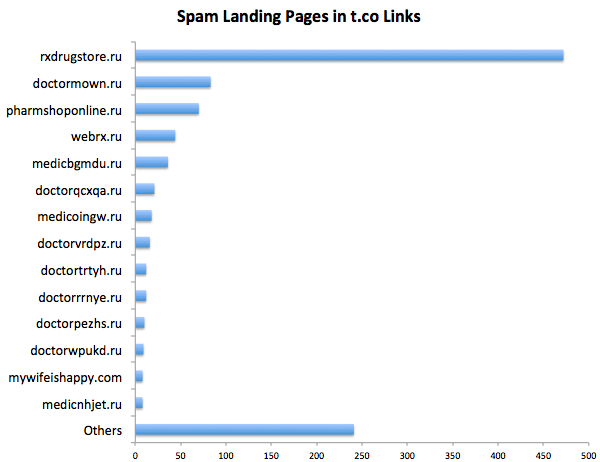

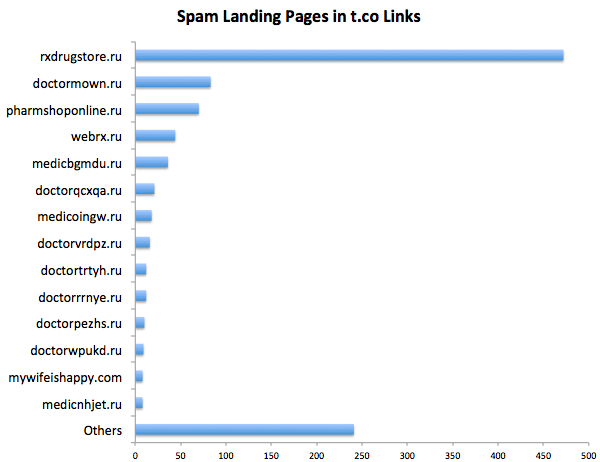

Let's take a look at those spam landing pages.

As you can see from the names, they are all bootleg pharmacy web sites. In fact, 80% of all the t.co spam landing pages I looked at were pharma sites. There were two distinct brands,

Pharmacy Express which accounted 22% of the spam landing pages, and currently uses domain names beginning with "doctor" or "medic"; and

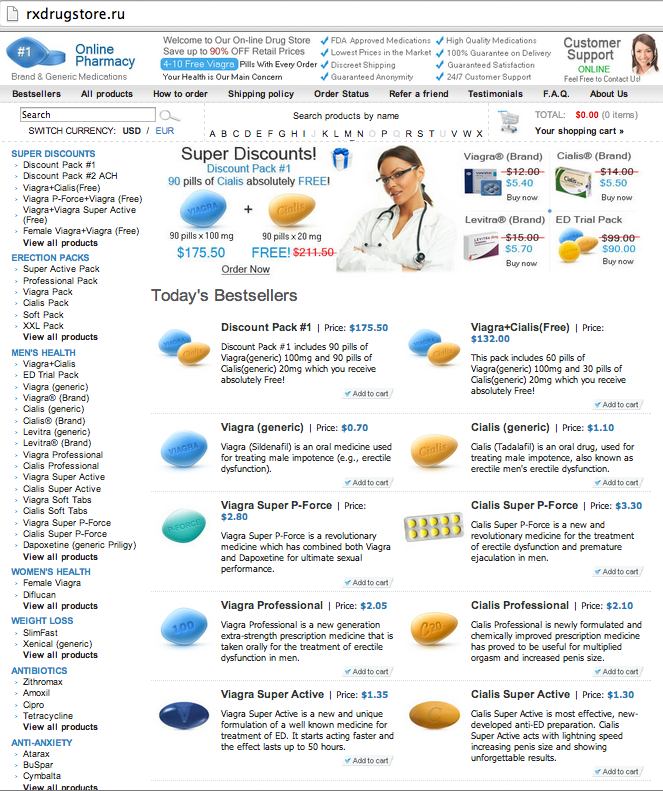

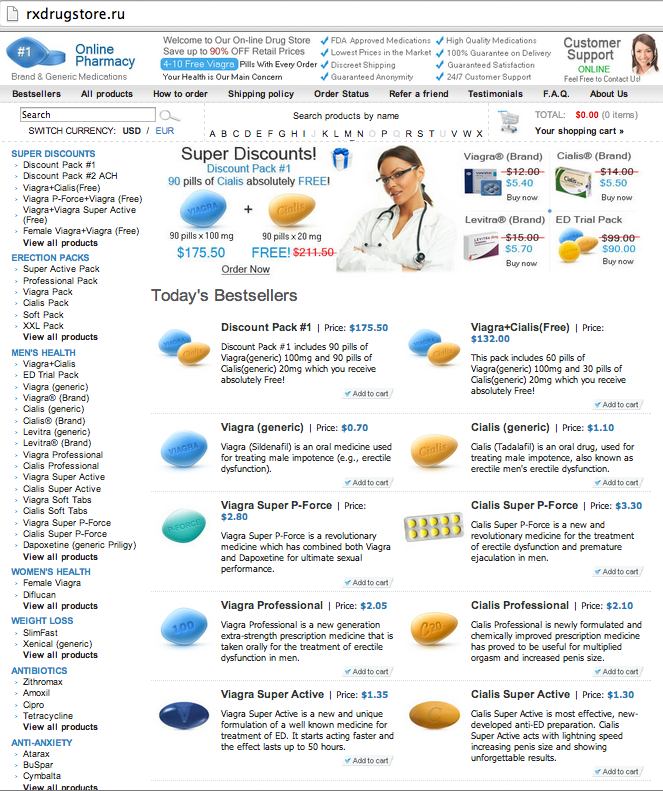

Online Pharmacy which was a whopping 58% of all the spam landing pages. Here's what they look like.

In spite of the maple leaf, neither of these operations have anything to do with Canada. They would long since have been shut down if they were. They are quite probably based in

Eastern Europe and selling bootleg drugs manufactured in

India.

Though there are two distinct brands, the techniques used in their spam advertising are identical, which makes me think that this is the work of a single spammer. Pharma gangs usually operate affiliate programs where spammers who advertise their sites get a percentage of the sales they drive. It's possible that one spammer is a member of affiliate programs for both operations. The other possibilities are that there is an exact copycat spammer, or one pharma gang is pretending to be two. However, I'm going to go for the simpler explanation that there is a single spammer behind all this.

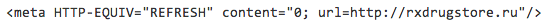

So how is this person managing to avoid Twitter's anti-abuse filters? With over four hundred t.co links redirecting to rxdrugstore [dot] ru in a sample of twelve hundred, you would think they might notice something. Well, the trick is that the t.co links do not go to the pharma landing page directly. They are using an intermediate layer of redirection. The t.co link redirects to a URL on a compromised domain, and that in turn uses a REFRESH meta tag to redirect to the spam landing page. This dual layer of redirection seems to be fooling Twitter. Compromised domains generally have good reputation and legitimate content on other links, so they are less likely to be blocked outright, but the spammer can use multiple malicious URLs on each one to redirect to his ultimate landing page.

Many of the same compromised domains are being used to redirect to

Pharmacy Express and

Offshore Pharmacy with different URLs. For example,

http://www.beautybycat.com/newwest.htm redirects to rxdrugstore [dot] ru, an

Online Pharmacy site, while

http://www.beautybycat.com/wild.htm redirects to doctorrrnye [dot] ru, a

Pharmacy Express site. This is more evidence that a single spammer is at work here.

This spammer is using a distinctive pattern for his malicious URLs. Each one is placed in the root directory of the web site, and consists of a single dictionary word followed by

.htm or

.html. The content of the file placed at the URL is a single line:

I'm sure that Twitter scans all t.co links at the time they are created. In fact when I tweeted the URL of my son's new

web site, within seconds the site was visited not just by a Twitter bot, but also by bots from Google and Yahoo!, so it looks as if they are monitoring Twitter activity as well. Given that, it is surprising that Twitter has not picked up on this particular abuse vector yet. The Meta Refresh redirection is highly repetitive and not obfuscated in any way. Perhaps the spammer places legitimate content on the compromised web site at the time he creates the t.co link, and replaces it with the malicious redirection after the link has been created? In that case Twitter would have to revisit the link when they detect a spike in usage, which should not be beyond the bounds of possibility.

Twitter does a good job of controlling spam on their own social network. In order to be responsible members of the Internet community they need to do an equally good job of preventing the abuse of their system to facilitate other forms of spam.