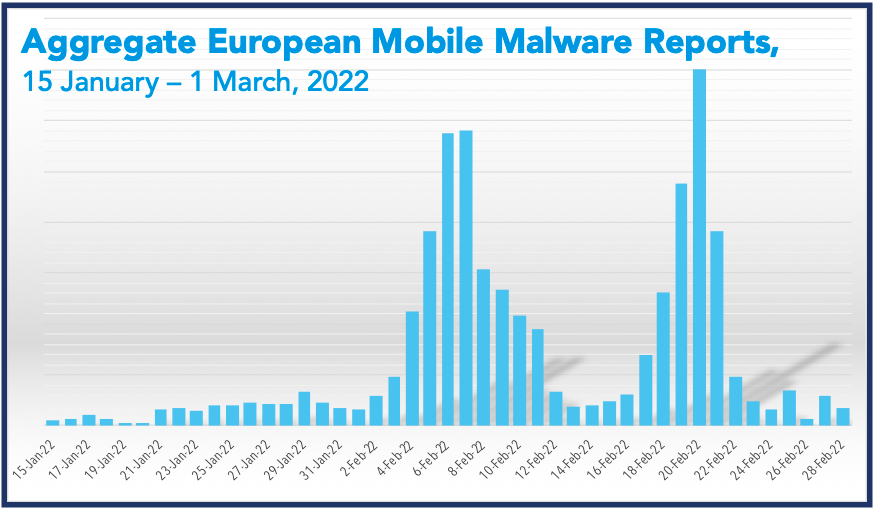

Starting in early February, our researchers detected a 500% jump in mobile malware delivery attempts in Europe. This is in keeping with a trend we’ve observed over the past few years where mobile messaging abuse has steadily increased as attackers ramp up attempts at smishing (SMS/text-based phishing) and sending malware to mobile devices. In 2021 alone, we detected several different malware packages across the globe. Although volume fell sharply toward the end of 2021, we’re seeing a 2022 resurgence.

Figure 1: Reports of mobile malware show significant spikes in February 2022.

Today’s mobile malware is capable of a lot more than just stealing credentials. Recent detections have involved malware capable of recording telephone and non-telephone audio and video, tracking location and destroying or wiping content and data.

Here’s a primer on some of the most common mobile malware our users are facing—and simple steps you can take to protect yourself.

Android vs Apple

Most mobile malware is still downloaded from app stores. But over the past year or so, we’ve seen an increase in campaigns that use SMS/mobile messaging as their delivery mechanism. Of the two big mobile smart phone platforms, Apple iOS and Android, the latter is a far more popular target for cyber criminals.

First, Apple’s App Store has strict quality controls. And iOS doesn’t allow sideloading—installing an app through a third-party app store or downloading it directly to the device.

For better or worse, Android takes a more open approach. The platform is open to multiple app stores. And users can easily sideload apps from anywhere on the internet. It’s this last feature that makes the platform popular with bad actors, who know that Android phones can be compromised in just a few steps.

State of mobile malware

At its core, mobile malware has the same purpose as its desktop counterpart. Once installed, the malicious software seeks to give attackers control of a system, potentially siphoning off sensitive information and account credentials. Where they have differed is mostly in delivery mechanisms and social engineering strategies.

That’s changing. As mobile malware grows more advanced, new kinds of data are being stolen, with potential impacts that are even more extensive. These include:

- Recording both telephone and non-telephone conversations

- Recording audio and video from the device

- Destroying or wiping content and data

A phishing/smishing link tries to trick the user into inputting their credentials on a fake login page in near real time. Mobile banking malware, in contrast, can lay in wait until the user activates a financial app. At that point the malware intervenes to steal credentials or information. All the while, victims believe they are safely interacting with the genuine banking app installed on their device.

Common Mobile Malware

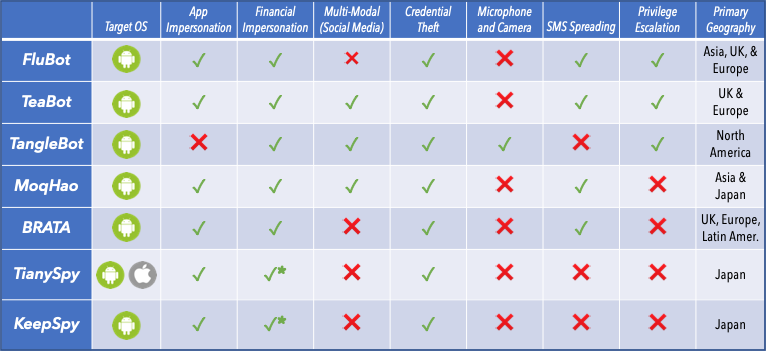

Mobile malware isn’t limited to any specific geographic region or language.

Instead, threat actors adapt their campaigns to a variety of languages, regions and devices.

Figure 2: Matrix of mobile malware types, functionality and regional spread.

Our Cloudmark Mobile Threat Research sees attacks spawning from regions around the globe, using a multitude of attack vectors to deliver malware to target devices. These attacks affect users globally and their scope and capabilities are increasing over time. Below we discuss a few of the prominent malware families using SMS as a threat vector.

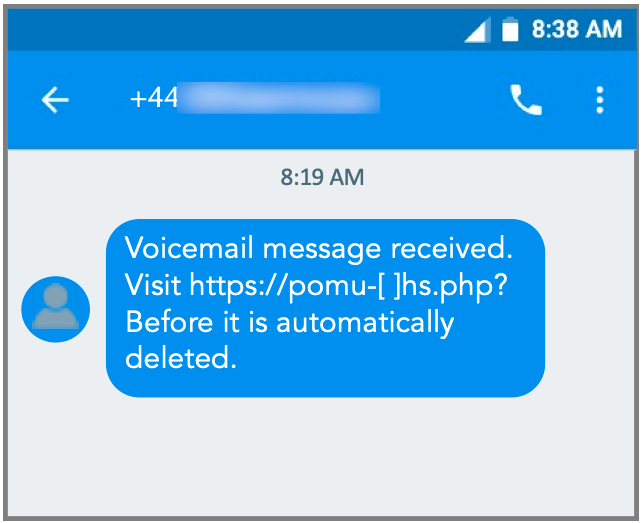

FluBot

This sophisticated, worm-like malware was first encountered in November 2020. Initial detections occurred in Spain before spreading to other countries, including the UK and Germany.

Since then, it been reported in Australia, New Zealand, Spain, Austria, Switzerland and other countries.

FluBot spreads by accessing the infected device’s contacts list or address book and sending the information back to a command-and-control (C&C) server. The C&C server then instructs the device to send out new infected messages to numbers on the list.

Beyond propagating itself, FluBot can also:

- Access the internet

- Read and send messages

- Read notifications

- Make voice calls

- Delete other installed applications

When targeted apps are used, FluBot overlays a screen designed to steal usernames and passwords from banks, brokerages and other sites.

Figure 3: A phony voicemail message used to distribute FluBot.

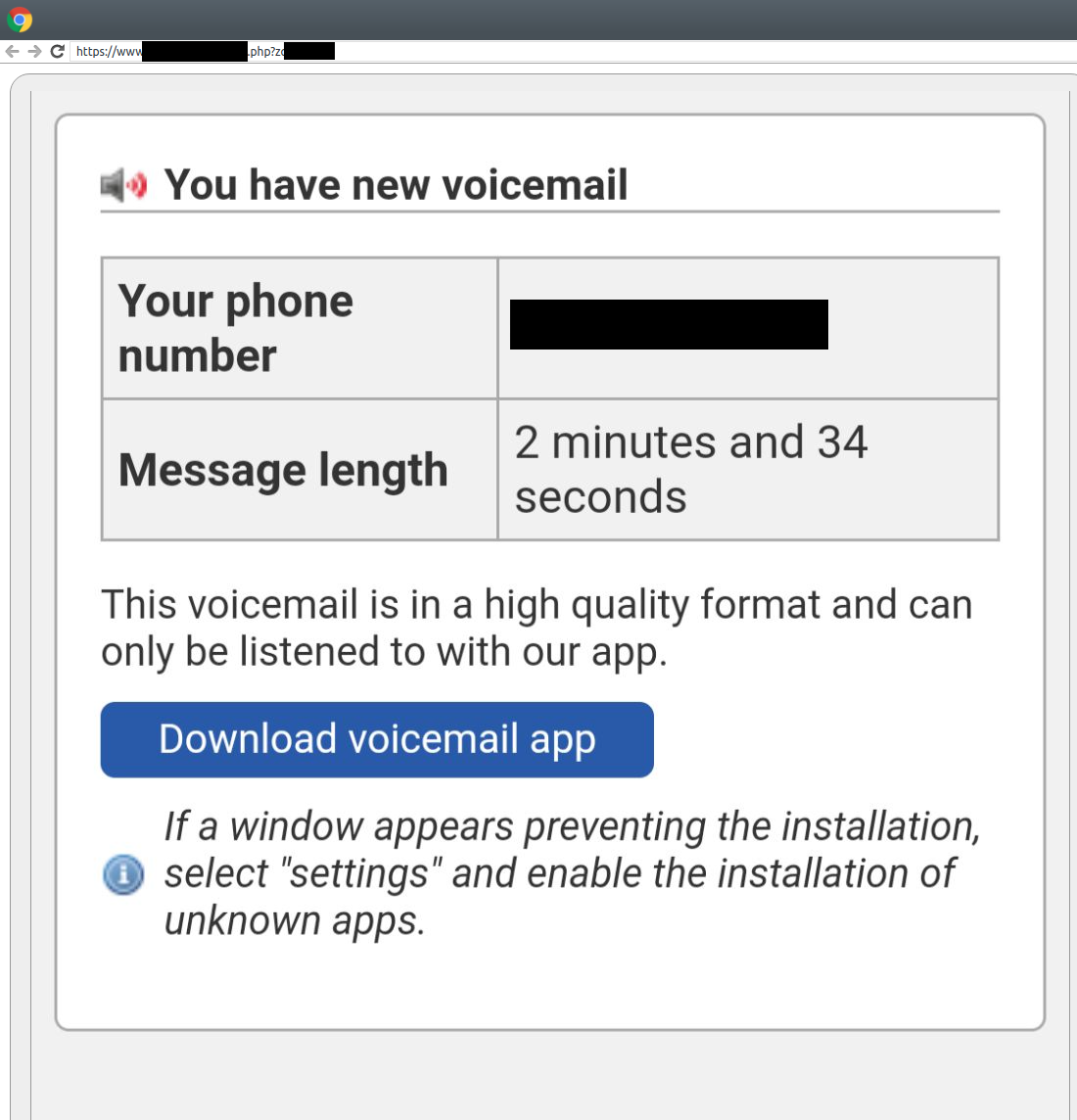

TeaBot

First observed in Italy, TeaBot is a multifunctional Trojan that can steal credentials and messages, as well as streaming an infected device’s screen contents to the attacker. It’s preconfigured to steal credentials through the apps of more than 60 European banks and supports multiple languages. It has targeted financial institutions in Spain and Germany.

TeaBot spreads using SMS messages similar to those of FluBot. TeaBot makes heavy use of keylogging and can intercept Google Authenticator codes. These two features make it a potent tool to compromise accounts and steal funds from victims.

Figure 4: A fraudulent voicemail download page used to distribute TeaBot.

TangleBot

Discovered by Proofpoint and Cloudmark researchers in 2021, TangleBot is a powerful but elusive piece of malware that spreads mostly via fake package-delivery notifications. TangleBot was originally detected in North America and has appeared most recently in Turkey.

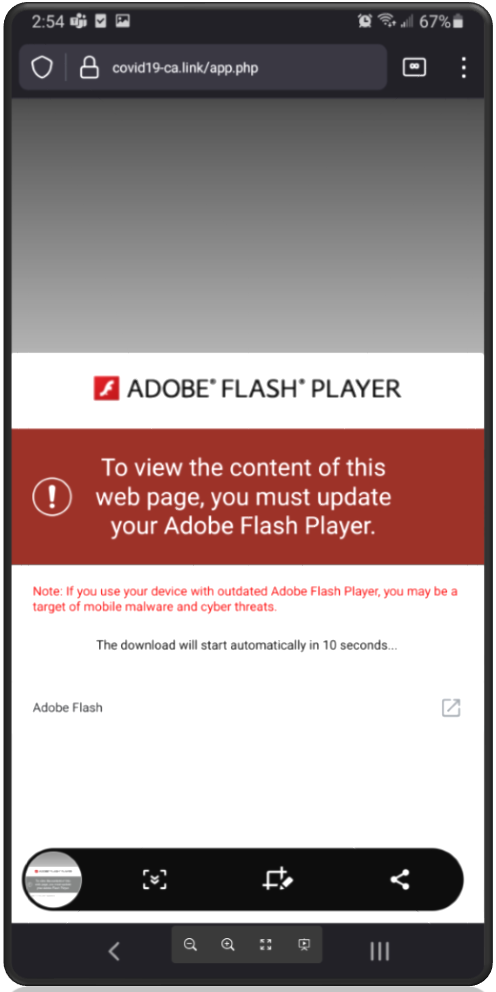

Now, the malware may be spreading through a collaboration between TangleBot- and FluBot-linked attackers. In both cases, the malware uses similar distribution methodologies, landing pages, language and SMS lures. One enticing lure that TangleBot has been known to use is a software update notification.

Figure 5: A fraudulent Adobe Flash update page used to distribute TangleBot.

Even with these recent reports, TangleBot attacks are still rare. But if it becomes more prevalent, the dangers could be substantial. Beyond its ability to control devices and overlay other mobile apps, TangleBot adds camera and audio interception to the mix.

At time of writing, researchers are uncertain as to why TangleBot has been seen in such small volumes. Malware is created by nefarious developers who often license their software to other criminals who actually run the attacks. Perhaps the initial detections were part of a test phase, demonstrating the malware’s efficacy to potential buyers. Or more ominously, they may be a prelude to bigger campaigns in future.

Moqhao

Moqhao is an SMS-based malware deployed by the China-based threat actor known as Roaming Mantis. It has been detected in several countries, including Japan, China, India, Russia and, more recently, France and Germany. These attacks are multilingual, with the website landing pages crafted in the target recipient’s language. Moqhao is a functional remote access Trojan with spying and exfiltration features. It can monitor device communications and grant an attacker remote access to the device.

BRATA

This mobile banking malware targets Italian bank customers, using SMS to lure them into downloading a fake security app. Once installed, BRATA, which is short for “Brazilian Remote Access Tool, Android” can record phone screen activity and insert app overlays to steal credentials. BRATA can steal user data (including usernames and passwords) and intercept multifactor authentication passcodes. This year, it has gained GPS tracking and device-wiping features that deploy after the data theft.

TianySpy

Targeting Japanese users, this mobile malware spreads by impersonating messages from the victim’s mobile network operator. TianySpy has an unusual feature that makes it a versatile attack tool: it can infect both iOS and Android, albeit through different mechanisms.

In Android infections, an added malware strain called “KeepSpy” is sideloaded. This step gives cyber criminals the ability to:

- Control and monitor Wi-Fi settings

- Steal information

- Perform web overlays

For iOS users, the attack vector is different. It uses a compromised configuration profile to exfiltrate the device’s unique device identifier (UUID). The attackers use the UUID to distribute the malware via a so-called provisioning profile. (Provisioning profiles are typically used by developers to test mobile apps before release and by corporations to deliver internal apps to employees.)

Protect yourself

The mobile malware landscape is fast moving, with new players and new capabilities emerging all the time. At the same time, social engineering tactics attackers use are constantly being refined. Awareness is critical—but many users still lack knowledge about the extent of the danger posed by mobile malware.

To safeguard your device, be wary of any unexpected or unrequested messages with links, URLs or requests for data of any type. And just as with desktops and laptops, it’s a good idea to use a mobile antivirus app from a trusted source. A recent Security.org study found that 76% of users don’t have one installed on their smartphone.

Finally remember to report spam, smishing and suspected malware delivery to the Spam Reporting Service. Use the spam reporting feature in your messaging client if it has one, or forward suspicious text messages to 7726 (“SPAM” on the phone keypad).

To learn more, check out the Proofpoint Threat Hub, your home for the latest research and insights.